The Book "That You Remain A Jew" Translated into Hebrew

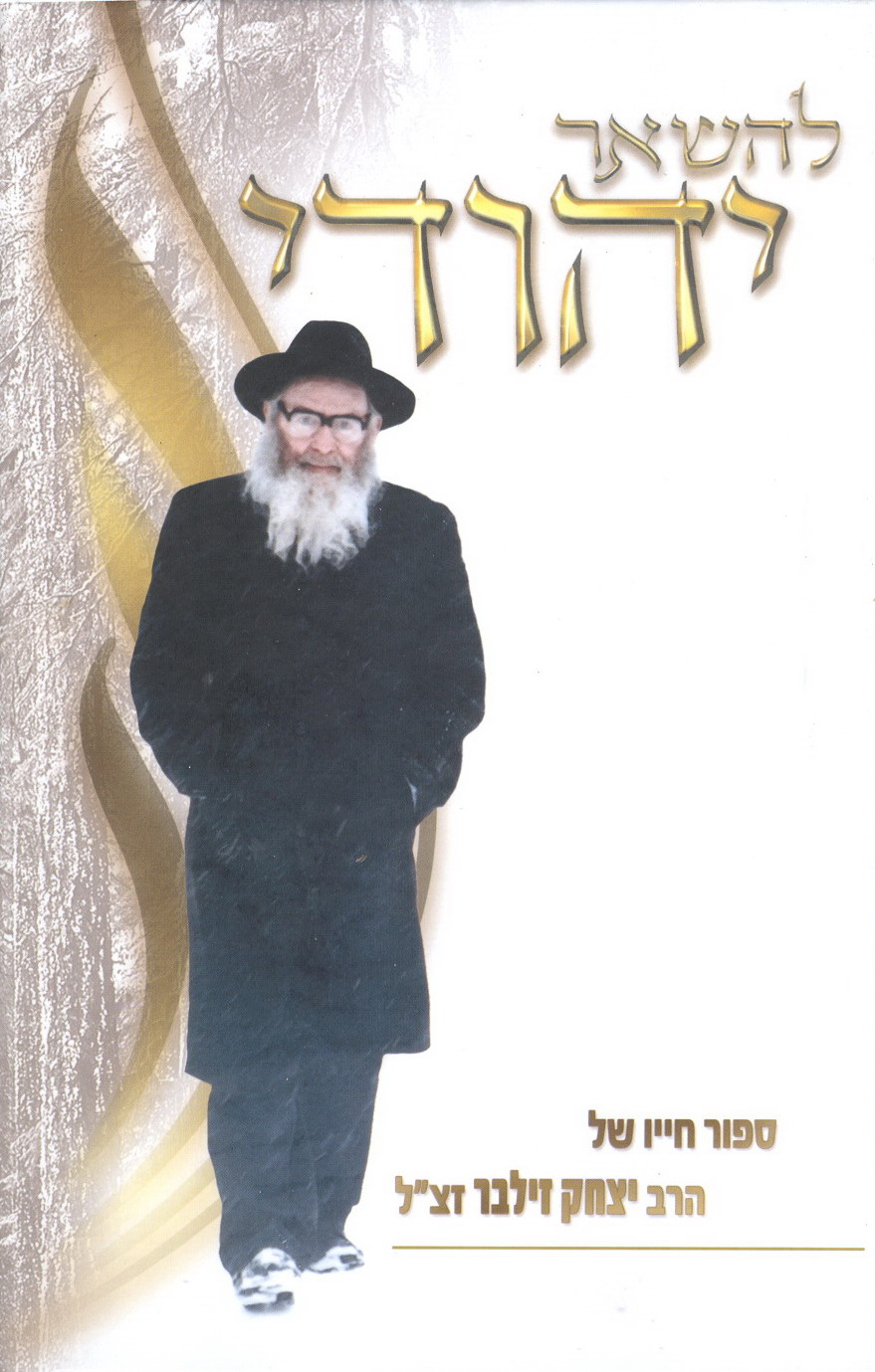

The autobiography of Rav Yitzchok Zilber, "That You Remain a Jew", is now available in Hebrew.

Today, on Av 8, 5767, on the third yohrtzeit of Rav Yitzchok Zilber zt"l, founder of the Toldos Yeshurun organization and leader of the Russian Baal Teshuvah movement, the Hebrew translation of his memoirs, "That You Remain a Jew".

The book can be purchased from Rav Ben Tzion Zilber as well as in many bookstores all over

The book has 436 pages with photographs.

HaRav Yitzchok Hutner zt”l asked Rav Yitzchok Zilber zt”l to constantly speak about his challenges in the Soviet Union, so that the example of his mesirus nefesh in keeping the mitzvos in the Communist Soviet Union could serve as an role model for contemporary youth. He implored him, “Be the Chofetz Chaim for the Russian Jews!”

Toldos Yeshurun has published Rav Yitzchok Zilber’s autobiography in Russian, and Feldheim will be publishing the book in English.

See also:

More in detail about the book (in Russian)

Presentation of the English translation of The Book

We are presenting you an exclusive preprint of an excerpt of Rav Yitzchok Zilber’s book.

The Purim that killed stalin - Purim 1953

We arrived at the new camp on a Friday night. Shabbos fell on 13 Adar (28 February), and on Saturday night came the holiday of Purim.

I gathered fifteen Jews and began telling them Megillas Esther — the story about Achashverosh, Haman, and the miraculous salvation of the Jewish people. One prisoner, Isaac Mironovich, lost his temper (he had a heavy heart — he was not young, and was serving a ten-year term). He almost flew at me with punches. "Who needs your ma’ases about what happened 2500 years ago? Tell me, where is your God today? Do you know what will soon happen to the Jews of the

I said in response, "True, our situation is difficult. But don\'t be in a hurry to eulogize us. Haman also sent orders for our destruction to 127 provinces. God will yet help."

"How will He help? Stalin already planned everything. This is not some Haman from long ago!"

"So what?" I replied.

Then he launched into a speech about how powerful Stalin was: he has already killed three million people and nevertheless achieved collectivization of the land, turning all of

I said, "True, he has always come out the winner, but that won’t be the case with us!"

"Why not?"

"Because it says: ‘The Guardian of Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps’ (Tehillim 121:4). And Stalin is no more than a human being, flesh and blood, a mere mortal.”

"But he is as strong as steel, despite his seventy-three years."

"No one can tell what will be with basar v’dam (flesh and blood) in half an hour," I answered.

Isaac Mironovich stomped off in anger. This was on Purim night, and in the morning he came looking for me. "Yitzchak, you know you said it good yesterday."

"What did I say?" I had already forgotten everything by that time.

“What do you mean? You said at 7:50 P.M. that Stalin is no more than flesh and blood, and no one knows what can happen to basar v’dam in half an hour. Today an engineer whispered to me that he heard on German radio that last night at 8:23 P.M., Stalin suffered a stroke and lost his speech. It happened half an hour after you spoke!”

We laughed at this coincidence.

On 5 March they officially announced the news of Stalin\'s death. His funeral was attended by the heads of state of the socialist camp, and among them the president of

As soon as I found out that Stalin was not well, I started to say Tehillim so that his end would come sooner. If today I know all of Tehillim by heart and can start saying any psalm from any point, then this is "thanks to Stalin." I went through them repeatedly for three days in a row, day and night: while running to get the water, clearing the grounds, or sitting in the barrack. I stopped only when I found out that he was dead. How did I remember Tehillim so well that I could say them by heart with such fluency? It was the Almighty who opened up my memory.

Can one say Tehillim for such a purpose? Yes, one can and should. It was absolutely correct to say Tehillim so that such a rasha should go quickly.

PREPARATIONS FOR PASSOVER

Purim passed. Not much time remained before Passover and we had to start preparations well in advance. Once I was asked, "Did you think there’d be changes after Stalin\'s death?" Was I waiting for changes? I was always waiting for salvation, I was waiting for Mashiach to come every day. With regard to Stalin, I neither spoke nor thought about him following his death.

I said to the Jews in my camp, "I cannot promise you that this will shorten our sentences, but we must try not to eat bread during Passover." In principle they agreed, but had no idea of how this could be done.

"The rations that we do already receive aren’t enough for us. If we stop eating them, what will become of us?" I said that I would ask my wife to get some flour and bake matzahs, and that we would try to get some potatoes.

Gita managed to get eight sacks of flour — altogether twenty-four kilos (fifty-three pounds). As I already said, this was not easy. But the main danger was that back then many people were imprisoned for baking matzah. They handed out convictions of eight to ten years. Nevertheless, Gita set about getting such a large amount of flour so that she could prepare matzah, not just for our family, but also for me, the other prisoners in camp, and a number of other Jewish families. A number of people approached her before the holiday, saying that the year was a difficult one and they were afraid to go buy matzos. They continued that unless she bought matzahs for them, they would have to spend the entire holiday without them.

Gita was saved from getting into serious trouble by a miracle. As she was tugging the matzahs on a sled, after baking them at a secret location, she was stopped by a Tatar policeman. "What are you transporting?" he askes. Gita had been accompanied by Reb Yitzchak Milner. But having noticed the police up ahead, Gita told him to leave, since a woman had an easier time making excuses. He left and Gita remained alone.

She started to describe her family, saying that she had two children and one had a birthday that day, so she was bringing home cookies.

"Why so much? Come with me to the police station!" the policeman ordered.

She tried to resist by delaying, so the policeman whistled and called over his colleague. They talked among themselves (they were speaking Tatar and Gita did not understand), then suddenly one came toward her and waved his hand, saying: "You can go!"

Gita concluded that this was so implausible that it had to have been Divine intervention.

At home Gita broke up the matzos into small pieces, wrapped them up in small sacks which she marked "tea cookies,” and succeeded in getting them to the camp. (The Shulchan Aruch, the compilation of Jewish law, which I mentioned in the beginning of this book, allows one to say the blessing Al Achilas Matzah on small pieces of matzah, if there are no whole matzahs available. The blessing can be said even on matzah dust and matzah flour.)

And so, matzahs we had. We even had maror — my wife, if I remember correctly, brought us horseradish. But how were we to get wine? It was completely forbidden to have it in camp. Fortunately I knew that if a person boils raisins and filters off the liquid, the Shulchan Aruch permits him to pronounce the blessing Borei Pri Ha-gafen (Who created the fruit of the grape vine) over it just as he does on regular wine. My wife made me such "compote" in the guise of a can of jam. I filtered off the liquid on the day before Passover, and this was enough for the four cups of wine which all participants of the Seder must drink, according to Jewish law.

How and where would I boil potatoes during Passover? I never ate in the dining room, always getting by with bread and tea, so there was nothing new for me to get used to. But what about the others? I borrowed a large pot from one prisoner and started cleaning it off with ice and sand so that I could kasher it later on. This was no easy job. As I sat and worked on the pot, Mishka Kosof came over to me. He was a pachan (a gang leader) among the camp gangs — a heavily built, handsome fellow, about thirty-five years old. He said to me in perfect Yiddish, "I am a Jew. I heard that you are planning not to eat chametz and I am with you." He handed me a 100-ruble bill. "I would like your wife to buy me a kosher chicken."

The Jews who were standing nearby almost fainted, and I myself was shocked. Mishka Kosof — a Jew? Mishka explained, "That the thieves think of me as a Russian works better for me."

Another problem we had to solve was where to store the matzah. Every closet was shared by four prisoners, and the place was full of thieves. I was asked, "How can we keep our matzah in the same closet where bread will be stored?"

I responded, "In the Torah it says, ‘…Nothing leavened of yours… may be seen anywhere in your domain.’ The closet is not your possession, and what is stored in it does not concern you." But this would nevertheless be unpleasant. Moreover, it was well-known that as soon as anyone received a package from the outside, he was immediately approached by gang members, and told that he had to give them a third — otherwise they would beat him up at night and take away everything.

Kosof showed some initiative in solving our problems. He was part of the camp drama group, had access to the cultural/educational facilities, and saw there a small, brand new dresser. He broke the door, stole the dresser, and brought it the day before Passover.

"Here is a drawer with a lock,” he said. “It’s completely clean — good for Passover."

Then he [Mishka Kosof] approached the gang and said, "Today and for eight days more, if anyone approaches Zilber and asks him ‘to share’ — he will lose his head." They knew that Mishka did not throw his words around lightly, and they did not approach me.

Mishka himself went through the torture of not eating chametz. He told me that he had already served time in

But where on the camp grounds, will you tell me, were we to conduct the Seder itself? I decided to take a risk and approached a Jew who worked in the medical facility. "You usually distribute the medications between 8:00 P.M. and 9:00 P.M. Would it be possible for you to do this from 6:00 to 7:00 for only two days? (Two, because in the Diaspora the first two days of Pesach are a holiday.) This prisoner from Bialostok was one of those men who had abandoned their Jewish wives, marrying non-Jewish women in their place. But how curious — once when I entered the medical facility I heard him singing to himself, “I have no complaints against You. God and His judgment are just" in Yiddish. He must still remember, then, that he is a Jew, I thought. He was willing to do what I had asked. He freed up the medical quarters for two evenings and sat with us, eating matzahs.

The

On the eve of Passover bread is not eaten from the morning, and towards the evening we were terribly hungry. So at 8:00 P.M. I went to get the matzahs from the storage area. I was still afraid to store them in the barrack, fearing theft. Mishka\'s warning to the thieves concerned only the expected "sharing" of the package. To guard oneself against regular thievery, though, was impossible.

The prisoner who manned the storage area, a biologist by profession, formerly a colleague of the famous scientist Ivan Michurin, treated me with complete trust. During the two years I was there, not once did he ask me to sign when I took something or gave in something: I simply gave in or received my things. But this time he suddenly demanded, "Sign!"

I was taken by surprise. "What happened? Why now?"

But he insisted, "You won\'t sign, you won’t get."

The holiday had already begun, and so writing was forbidden. I pleaded with him for over an hour. Until this day I do not know what his reasons could have been. A test from above, I think. With much effort I finally got him to give me the matzah without signing anything.

And so, on the evening of Passover we entered the medical quarters. We sat behind the table there like kings. We drank the wine and ate the matzahs, reading the Haggadah that Communist Party secretary Vishnyov had brought me half a year ago. There were as many of us as could fit into the room, I think twelve. I invited my closest friends.

And what about the rest? I gave them matzah, advised them to get together, and taught them to say Kiddush. Before the holiday I was approached by a number of other people I did not even know were Jewish. They asked, "Give us a kezayis of matzah." One of them said that he had been imprisoned for a very long time, since the war, when he worked as a Kapo — maybe in a ghetto or a concentration camp. He confessed that he had not eaten matzah already for twenty years. We gave out pieces of matzah, so everyone had a kosher Seder!

I explained to them that during the Seder one must explain why we brought the Pesach sacrifice, why we eat matzah, and why we eat bitter herbs. The commandment is to discuss these things while sitting down comfortably, leaning to one side, in a manner which is fitting for a free man. Everyone did this.

I will never forget this night. Mishka Kosof sat with us in the medical facility, drank the four cups of wine (he was ecstatic over our wine), and ate matzah as everyone laughed, "Mishka Kosof became a Jew!"

OUR Passover “Kitchen”

Well before the arrival of Pesach we had to decide where and how to cook our food. Pesach is a spring holiday, and they had already stopped heating the barracks. They kept on heating only our barrack, for some reason. However, the man in charge of the heat would not allow any of us to get close.

Having noticed that he sold dried bread, I bought some from him a couple of times, even though I did not need any. The third time I did not pay the full sum right away, and then showed up to pay what I owed him when he was stoking the stove. I gave him some matzah to taste, and afterwards he let me come in freely to cook. It was unbelievable, but only in this block did they heat until after Pesach.

Given that I was always looking for people to substitute for me on Saturdays, I made quite a few friends among the criminals. (I even learned their jargon and songs. I sing them on Purim and on the Seder night.) I arranged that they would ask for some raw potatoes from the outside (I had already exhausted my own quota for receiving packages from the outside). Every day at 5:00 A.M. I peeled and cooked potatoes: at 6:00 everyone was driven out to work, so I had to have finished cooking by then. Without salt, without anything — we only had potatoes. If I managed to cook the potatoes, the prisoners ate them; but if not, they left for work hungry.

They held on for real! They came again to me at lunch. If I had potatoes, most would remain and eat, and if I did not, some of them went to the dining room. I begged them not to eat the hot cereal, but only the potatoes. This is how we made it to the end of Passover.

On the first day of Passover I stood over the cooking potatoes, guarding and making sure that no one touched them. Next to me, two Udmurt men — those hoodlums — were cooking pasta, as if on purpose! According to Jewish law, if kosher and treif foods are cooked near each other there is no problem. Suddenly though, one of them, after mixing the pasta, put his spoon straight into my pot with the potatoes! Can you believe it?

What was I supposed to do now? The potatoes were ruined and what about the pot? I was again saved by my knowledge of Shulchan Aruch. I remembered that it is written there that the Ashkenazic custom is to be stringent and not use such a pot even after koshering it. I assumed that when there is no choice and no other means are available, one could continue to use such a pot and eat the potatoes cooked in it. I myself no longer ate the potatoes from this pot until the last day of Pesach, but I kept on cooking with it for the others. I did not tell them anything — what would that accomplish? As long as they did not know, the responsibility was mine alone. (Later, after leaving the camp, I asked two big authorities on Jewish law, and they said that I had acted correctly. But back then…)

I also was not very hungry — some water, some matzah. Looking back, I barely believe that all of this happened to me and I still remained whole and unharmed.

Every day I was searching for potatoes; finding them was unbelievably hard. I approached one person, a second, a fifth. Eventually I got some potatoes. I was both dragging the water and boiling those potatoes sometimes until midnight. Once, with great effort, I got my hands on some potatoes and cooked them. I was carrying the pot, it was spring, and the snow was thawing. I slipped and fell, and the potatoes rolled onto the dirty snow. I gathered the potatoes, cleaned the snow off them, and put them back into the pot. Should I tell everyone that they fell out or not? The people were hungry — they had worked until 12:00 or 1:00 in the afternoon — and their only food was the potatoes and a piece of matzah. They would probably be put off by the potatoes, so I did not say a thing.

Then came the eighth day of Passover. There was nothing left to eat, not even a crumb of matzah. Issac said, "But today in

"True,” I replied, “but we, here in the Diaspora, must observe one extra day."

He said, "I have no strength anymore… I can\'t go on. I want to eat bread now!"And here I witnessed the power of a simple Jewish custom. Not even a law, just a custom. On the last day of Passover it is customary to pray for the souls of one’s deceased parents. He remembered this himself.

"Wait," he added, "today the Yizkor prayer is said! To eat bread now and then recall the memory of my father with the same mouth — that is not right. I\'ll say Yizkor first."

So the two of us said Yizkor together. Others approached us, and among them one very unpleasant fellow. His father and mother asked that he neither say Kaddish nor Yizkor for them after their passing. They told him straight out, “Don\'t shame our name with your dirty mouth.” Why? Because he closed down the synagogue in his town, jailed the shochet and the mohel, and always maintained that all observant Jews were really frauds. He was like that accountant who I already mentioned. He, too, came to say Yizkor! He asked me whether he was allowed to do so. I follow a rule — I try not to hurry with an answer. I thought about his question and said, “Yes, you are allowed to.”

Then he asked me, "Is one allowed to eat herring and butter today?"

I laughed in response, "Where, here or in

"I received a package from home — herring and butter, and if I can, I will give it to you," he said.

At this moment we were approached by Isaac Moiseyevich with a piece of news: the anti-Semitic placards had been taken down. If they had removed the placards, that meant that the doctors had been freed. For a long time we did not know anything, but later I found out that they had been released on the second day of Passover. In the Talmud it says that redemption usually comes to the Jewish people in Nisan, the month of the exodus from

That day we ate herring and butter. We eventually got our hands on some potatoes, and I also ate from that pot — on the last day of Passover some leniencies can be allowed. This was delicious beyond description.

Then we strolled around the camp, enjoying the absence of the nasty placards. I was telling my companions stories from the Talmud, when we were approached by Volod\'ka Epstein — once a hard core atheist and an internationalist. I already mentioned his brother Maxim and the changes he underwent over time. The camp changed Volod\'ka as well. Before Passover, when we were in need of people who would agree to receive packages of matzah (in the form of tea biscuits, of course), he agreed to help us out and served as a recipient. Upon leaving the camp he changed his whole life around — he parted with his wife and married a Jewish woman. This was a difficult step.

Volod\'ka announced that today in the evening he was supposed to receive a pot of jam, and that he was donating the pot to those who did not touch bread during Passover. Those who ate bread even once should not bother coming. A pot of jam! At the camp, one can exchange who knows what for an onion, and here there was jam! In the evening following Passover everyone came to him to drink tea with jam. I did not go; I wanted to be alone. This is how Passover ended. And immediately thereafter they announced amnesty.

See also: