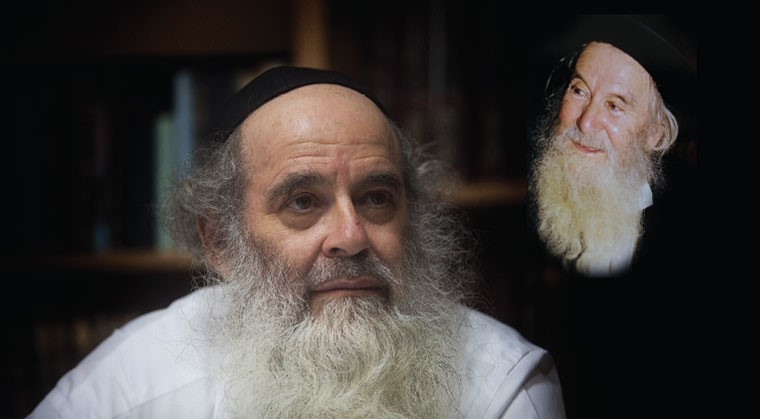

Rav Elyashiv named Rav Yitzchak Zilber one of the 36 hidden tzaddikim of his time. Rav Bentzion Zilber’s homage to his father’s exemplary fortitude

There’s an underlying question that jumps off the pages of Rav Yitzchak Zilber’s best-selling autobiography, To Remain a Jew. While so many Soviet citizens sunk into the mire of G-dless Communist ideology during the decades following World War I, what gave Rav Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Gita Zilber the wherewithal not only to barricade their doors against the spiritual onslaught from the outside, but to raise their four children in Communist Russia as if it wereJerusalem?

In conversation with Rav Bentzion Zilber — only son and successor in leadership of the Russian-Israeli kehillah Rav Yitzchak ztz”l built — we get a peek into the seemingly simple but extraordinary home of his parents, and hear his own homage to the exemplary fortitude of his father, a man named by Rav Elyashiv as one of the 36 hidden tzaddikim of his time.

Rav Yitzchak, who passed away in 2004 at the age of 87, was considered a malach among Russian Jews, inspiring them with his own mesirus nefesh for half a century inKazanandTashkent, and after that as leader of the Russian teshuvah movement in Eretz Yisrael.

In the shadow of the KGB and the Gulag, the Zilbers managed to raise their children with similar backbone. When they had to be out of the house, little Sarah (Zavdi) and Bentzion already knew how to answer snooping KGB agents. Rav Bentzion, who’d managed to learn portions of Shas by heart while growing up under Communist oppression, was only 14 when he kept Torah and mitzvos for months alone in a Russian sanatorium — hiding his tefillin in a tree. When Chava (Cooperman) immigrated to Eretz Yisrael and joined an Israeli Beis Yaakov, her knowledge of Chumash was on a higher level than her new peers.

How did they do it?

“It’s a good question,” says Rav Bentzion, who prefers conversing in Yiddish to Ivrit or Russian. “I can tell you what I think. My father had very brave and choshuveh parents, and that was transmitted to him. The Zeide [Rav Bentzion Chaim Zilber, rav of the town ofKazan] was a Slabodka talmid, so Tatte received that Slabodka education — a lot of chochmah, a lot of breitkeit [broadmindedness].” Rav Bentzion Chaim refused to send his brilliant son to an anti-religious Soviet school, and instead taught him privately at home, where he became well-versed in all areas of Torah, as well as secular topics. By the time Yitzchak was 15, he was teaching Torah to other Jews even though it was illegal, and his genius gained him entrance to theUniversityofKazandespite never having attended school, where he trained as a professor of Mathematics.

My father wanted to serve as a rabbi without being paid and decided to earn money through trade. He gave all of his money to a few businessmen to invest. When their business started showing a profit, my father found out that his partners were trading on Shabbos. He refused to take “Shabbos money” and had to accept the post of official rabbi. I remember the seal he kept at home that said “The Rabbi of Kazan Gubernia (District).”

From morning until night my father was involved in community matters: from noon to 2:00 PM daily he supervised shechitah at the city slaughter house, then he would teach people in the synagogue, accept visitors at the synagogue and ultimately at home, answering their questions and giving counsel regarding their problems.

When in 1926 the Soviet regime wiped out everything connected to Jewish religious life and closed the synagogues, my father's activity became unofficial and underground. How did we manage to live after that? Don't ask. (From To Remain a Jew)

Rav Yitzchak and his wife Gita (nee Zaydman) passed the torch to their own children using much of the same technique. “We were educated from our younger years with seichel,” Rav Bentzion says. “My parents did not just give instructions — they explained the meaning behind our Yiddishkeit. We didn’t go to kindergarten — I first went to school when I was eight — so that by then we understood that the home was the center of our lives, not the street. I played with non-Jewish children outside, but never developed a real bond with them. Our ‘real’ life was at home.”

On the Russian street, the populace worshipped first Lenin and then Stalin, but inside the Zilber home, among a handful of holy, stubborn Jews, the family worshipped G-d. The children never doubted their parents’ views.

“Our parents were devoted to us,” Rav Bentzion says, his voice carrying a softness that still reflects a virtual blanket of love and security 60 years later. “We were never rich, but my mother made our home geshmak — comfortable and happy for us. I can tell you that the main koach of chinuch is the kesher between the child and the parents. A geshmake, nunter [close] kesher. That’s what our chinuch was made of.”

His Good Eye

Rav Yitzchak Zilber was initially raised in a 12 square-meter room, part of a government-owned apartment in his birthplace,Kazan. The main room of the apartment was allocated to the Yevsektsiya, the Jewish section of the Bolshevik party, whose purpose was to “build socialism” among their people by mercilessly destroying all remnants of Judaism. In the early 1930s, when Yitzchak was a teenager, it was decided that by being a rabbi, his father had forfeited his right to vote, and to an apartment. The “dispossessed” parents and child were literally thrown out onto the street.

The gloomy drudgery and constant stress of daily life in a police state, even without the added pressure of practicing an illegal religion, sent many Russians to a despondent suicide. Was Rav Yitzchak ever beaten down by the weight of his lonely struggle? “Sure, my father had his very shvere tekufos,” Reb Benzion says. “The persecution in Kazan, when everyone, including colleagues, testified against him, and my parents’ real fear that they would take the children away, was very difficult. But he never let go of his positive attitude.”

In the 1950s, a search through the Zilber house revealed some illegal papers left by another Jew. Rav Yitzchak would not denounce a fellow Jew, so he was arrested and imprisoned. The owner of the papers, shocked that the rabbi was imprisoned on his account, went to the police to admit his responsibility. The KGB gladly imprisoned him too, and Rav Yitzchak’s case turned into a trial for conspiracy, with a much harsher sentence.

Even in Stalin’s gulag, the heavy menial labor and cruel conditions of the prison camps would not deter Rav Zilber from keeping Shabbos, the mitzvos of Pesach, Chanukah, Yom Kippur and other sacred days, or from teaching Torah to other prisoners. He was eventually released from prison and was permitted to return toKazan. But while not openly violating Soviet law, he was harassed by the KGB and both he and his wife were fired from their teaching positions. The Soviets even attempted to take away their children. Upon receiving a summons to KGB headquarters, Rav Yitzchak fledKazantoTashkent, where he was eventually able to move his family. For years the family applied for emigration toIsrael, but were constantly refused — until they finally received permission in 1972.

Rav Zilber’s positive attitude and ayin tovah even in the face of his adversaries made him into a magnet of influence. “When my father was in prison, conditions improved a bit after he was finally sentenced,” remembers Rav Bentzion. “So in a letter to my mother he wrote, ‘It’s good here. We get taken for some walks outside, and we can go to the bathroom when we want.’ My mother used to say that some people don’t write such happy letters from vacation as my father wrote to the family from prison. He lived with such a geshmak, such simchas hachaim and endless positivity.”

Denounced as a saboteur and a parasite by his own colleagues, with whom he had taught with utmost diligence for decades, this ayin tovah stood Rav Yitzchak in good stead.

“My father was blessed with great gifts in addition to his love of Torah. One was humility, the ability to forgive any personal insult — unbelievable how my father could forgive. I saw with my own eyes — there were people who demeaned him or who informed on him. He held no grudge and spoke well of them instead. I was once with the Tatte inTashkentwhen someone attacked him verbally. No sooner had the man left that my father turned to me and pointed out some of his assailant’s finer qualities.”

Rabbi Avraham Cohen, director of the Russian kiruv organization Toldos Yeshurun which Rav Yitzchak Zilber founded when he was already in his 80s, once asked him: “Why have you merited lengthy days?

“The Rav was in a very good mood on that occasion — his granddaughter’s engagement,” says Rav Cohen, “and he replied candidly to me ‘I never in my life told someone “you are wrong.” I was extremely careful never to shame anyone, and in that merit, I have received long life.’ Then he tacked on a story. ‘Once in my life, I did rebuke someone, and I always regret it. It was when I was imprisoned in Stalin’s labor camp. In order to keep Shabbos, I became the camp’s water carrier. On Friday, I had to draw and carry the water supply for the whole camp to use over Shabbos — five huge cisterns. One Friday afternoon, a huge one-handed man, a fellow prisoner, went and spilled out all that water. It was an extremely difficult and painful situation [since if there was insufficient water over Shabbos Rabbi Zilber would have been punished or killed.] I said to this gentile “Why?” and I regretted it afterwards. He continued to hate me and made a lot of difficulties for me. Other than that one time, I never told anyone off or that what they were doing was wrong.’ ”

Rav Yitzchak kept up this supreme delicacy of speech and friendly manner to everyone throughout his life. At one shabbaton for Russian Jews in the northern town of Nahariya, Rav Zilber was walking and met several people smoking cigarettes. “As he met each person, he began to chat about how nice the weather was and how nice it was to be in Israel. He spoke about how lucky we are to be Jews…. He didn’t tell anyone that it was wrong to smoke, that they were doing something which is forbidden, but one after the other, ten people threw their cigarettes away,” Rabbi Cohen marvels. “He knew how to penetrate another’s soul — and that’s why people listened.”

Riki Goldstein, http://mishpacha.com/